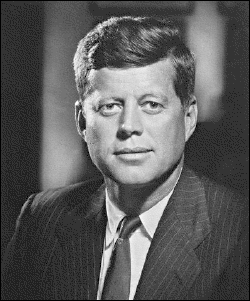

When you see this photo, do you think “John F. Kennedy”? That was caused by your brain.

People act the way they do because of their brains. For example, when you put your shoes on, do you put your left on first, your right on first, or do you do sometimes one and sometimes the other? This is caused by a mind module, a kind of conceptual routing program, that controls the order in which you put things on your feet. Everyone has this “Calciatus Arbitrium,” which evolved when the first cavemen began cutting old automobile tires into strips and attaching a thong of woven polyester, thereby creating the first primitive sandals (fortunately the prior evolution of the “Secofascia Adjunctus,” the module that governs cutting things into strips and attaching things to them, allowed them to do so). These sandals are used to this day in many countries—evidence of their near-perfect design. Try it the next time you put your shoes on; you’ll find that you either put your left or your right shoe on first. This is an example of universal innate behavior. We know it’s universal because it’s innate, and we know it’s innate because it’s universal.

Have you ever walked into a store and bought something? That was caused by your nucleus accumbens, located where the caudate and the anterior putamen meet, just lateral to the septum pellucidum. It controls consumer behavior. MRI scans of shoppers reveal high rates of glucose metabolism in their nuclei accumbens. Have you ever walked into a store and left without buying anything? That was caused by your amygdala, located in the medial temporal lobe. The amygdala governs the fight-or-flight instinct, which is activated when you are confronted with a choice to fight or flee, which is controlled by the amygdala.

Language provides many fascinating examples of cognitive psychology. Have you ever typed “teh” when you meant to type “the”? That’s because the word “teh” is stored in your brain very close to the place where “the” is stored. When you reach for one, you accidentally grab the other. When you see a photograph of John F. Kennedy, your brain automatically summons the words “John F. Kennedy”—this is because photos of Kennedy and the name “Kennedy” are stored near each other in the brain. We know this because people have a tendency to think “Kennedy” when they see a photo of Kennedy. If you don’t, it’s probably because of your hippocampus.

Speaking of the hippocampus, it controls memory, and there are many types of memory: implicit, explicit, procedural, short-term, long-term, semantic, motor, sensory, autobiographical, episodic, involuntary, flashbulb, echoic, eidetic, iconic, and visual. These types of memory are all natural, evolved, independent, inherent features of the human brain. It is definitely not the case that there is no evidence for them except the phenomena they were invented expressly to explain.

Cases of the power of the mind over the body are too convincing to ignore. For example, ulcers are caused by stress. A person could be walking along, feeling great, on top of the world, and then, with no change in his or her environment, he or she could suddenly be stricken by stress, which will cause an ulcer. (A related phenomenon is when a person suffers a run of bad luck—the death of a loved one, a failing business venture, persistent unemployment—and begins feeling stress, which causes the ulcer, but scientists agree that it was the stress, not the negative events, which was the true, ultimate cause of the ulcer.) Or if a person sees, says, a huge engaged grizzly bear charging right at them, he or she will often feel afraid, and will then run away. The feeling of being afraid actually causes the person’s legs to move!

As you work your way through the textbook you are now holding, you may feel trepidation, which may cause frustration, which may in turn cause either apathy or anxiety, but fortunately those things can be countered with motivation. There are two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation is much better to have, but don’t worry if you don’t have it, because by undergoing a series of training procedures, you can actually build up your intrinsic motivational powers. Confidence can also help you achieve motivation. Studies show that confident people have often succeeded at things in the past, so clearly confidence caused those people to succeed. Confidence comes from within, and you can acquire more of it by succeeding at things.

Good luck!

2 Responses to Introduction to Cognitive Psychology: An Introduction